Things That Go Bump in the Night

When I was a child, I had a recurring nightmare. An alarm would go off in my house, known as the Zorro alarm (no connection to the hero, except that perhaps I’d seen the film one too many times). When this alarm went off, me and my parents would have to bundle ourselves into the attic and remain completely silent as a man in a large hat (Zorro, presumably) and a plague doctor mask (a bizarre retelling?) crept through our house. If he found anyone, they would be taken – where, I don’t know. Sometimes, my dad would want to go down too early. I would beg him to stay, to wait just a bit longer until we knew that he was gone. Sometimes, he would listen. Sometimes, he would go down, and when we later emerged from the attic, Zorro would be gone – my dad along with him.

We all remember the things that frightened us when we were young. Most of them are tangible fears: spiders, or clowns, or the dark. While my Zorro dream wasn’t exactly tangible, it was all rooted deep in the real fears and insecurities of my waking life, although I perhaps wasn’t aware of it at the time.

I don’t think I’ve had that dream since I was in my early teens. Somewhere in the process of growing up and growing older, fear became different. It was no longer the tangible that served to send an unnerving chill down my spine.

The dark comes every night but still serves to unsettle.

Fear, for the large part, morphed into anxiety and panic. I didn’t fear things so much as worry about them, relentlessly. Sociologist Allan Horwitiz has studied the relationship between anxiety and fear and describes fear as anxiety attached to one specific thing. When my fears became less clear-cut and easy to define, anxiety took over the general bubble of all things troublesome.

Some of the things we might acknowledge as fear in our younger selves also just become a dislike. As a child, I would have said I was scared of big rollercoasters. Now, I know that it’s not that I’m scared of going upside down on a rollercoaster – it’s that I don’t like going upside down on a rollercoaster because it makes my head feel weird.

Now, if people ask me what I was afraid of, it would be the all-encompassing worries that are, I think, common of your late 20s. It’s the fear of failure in your career, the fear of ending up alone, the fear of financial instability. 2020, incidentally, has not helped with any of those.

In the same way a nightmare would, these fears can keep you up at night. They can fill your mind and distort your focus and make the thing seem far worse than it is. Fear niggles into the cracks we don’t notice and makes a nesting place that becomes difficult to uproot.

Those fears are harder to shake. You can’t just open your eyes to the cool light of morning and know that there is no man trapping you in your attic, waiting to snatch you or your family members away. Maybe that’s why we seek out tangible scares as adults, for the adrenalin rush of knowing that it’s not real. That it won’t hurt us.

For me, the greatest adrenalin-spiking fears have always come from the immersive headspace of certain escape rooms. (Not the horror-themed rooms – with all due respect to people who enjoy that kind of thing, you couldn’t pay me to go in one of those). Lost in a puzzle that I know is fake but seems impossibly real, I have more than once been frightened out of my skin by an unexpected interruption from a guide. Last year, a few friends and I went to an outdoor immersive escape “room” where we ran wildly around a pioneer village collecting clues while cultists in long robes and full-face masks stalked us from every corner. They could not touch us, they could not harm us, they didn’t even speak. They just… Appeared. I was hoarse by the time I got home from screaming. The adrenalin high was immense.

(Those ones were actors and didn’t).

These are easier fears to confront. At the end of the night, we drove home and the cultists were just actors in masks who went back to their everyday lives.

Fear can take darker, crueler forms, too. People often talk about prejudices as coming from a fear of the unknown, or of the different. Change can certainly be scary, and that which we don’t know can cause us anxiety. This year has incited fear because, truly, no one could quite predict what would happen next. They could guess but no one could be sure. Because we had never done it before. It was unknowable.

But to excuse prejudice on the basis of fear is to give fear too much credit. We are all affected by fear in some way, at some point in our lives, but we should not be controlled by fear. Especially if we will allow that fear to affect our words and actions.

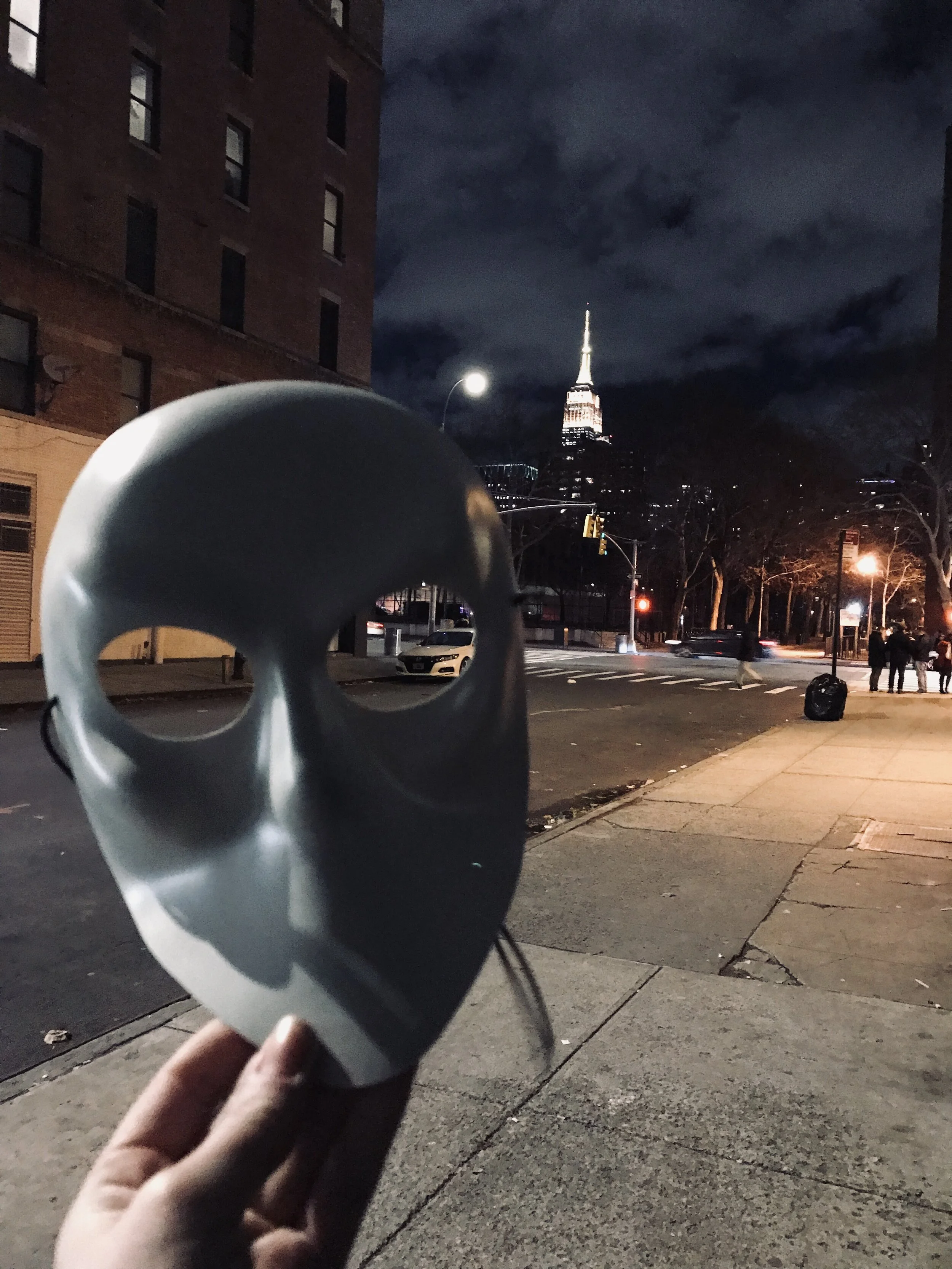

My most tangible, lasting fear is of full-face masks, where you cannot see a person’s eyes or mouth. It removes an element of humanity that makes the average stranger that much more sinister. It took me a while to adapt to seeing faces shielded behind masks as an everyday occurrence and I often found myself searching out their eyes. Sometimes, a flicker of shared understanding passes in that moment of eye contact, a glance enough to say, what a year, huh?

Spending a whole night in a full-fask mask, surrounded by people in full-face masks, was a lot on my sense as it was. (Sleep No More, NYC, Dec 2018).

This year has been the scary. For the unknown. For the unseen yet deadly. For the looming question mark of what comes next. If just for today, I’ll revel in tangible fears of spooky films and a Halloween night in the dark.